The majority of the Police Officers in England and Wales are employed by one of the 43 territorial Police Forces named after the ‘shires’ into which the country was traditionally subdivided for the purposes of local government e.g. Leicestershire, Kent, Norfolk, Devon and Cornwall – along with broader entities designed to reflect the biggest urban conglomerations such as West Midlands, Greater Manchester, Merseyside – and of course the Metropolis itself. I have successfully sued every single one of these 43 Police Forces.

Despite their regional designations, the Policing powers of each Force are not geographically limited, and Forces often mount joint operations together. The powers and privileges of an Officer of Lancashire Constabulary do not disappear when he crosses the line into a different county.

The Police Constables of each specific territorial Force are all, ultimately, ‘Police Constables of England and Wales’, answerable to the Home Office. An off duty Metropolitan Police Officer, travelling on a train through Hertfordshire, can put himself on duty and exercise the full powers invested in him by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) if he detects, or believes he has detected, a criminal offence taking place.

But this is not the case with every type of Police Officer. There are also a wide variety of ‘Special Police Forces’ whose Officers, despite the title and uniform they bear, are not full Crown Constables but – in reality – glorified security guards employed by, and answerable to, those Companies or Corporations which own/run a specific location or type of infrastructure, most commonly a transport hub. These Police Officers are invested with the powers and privileges of full Constables only for the specific purpose of policing and protecting their particular infrastructure. Generally, they are not allowed to exercise their powers beyond the geographical boundaries of that infrastructure.

For example, the Port of Dover Police, as with many other ‘Harbour Cops’, are funded by the owners of the Port and derive their powers from the Harbours, Docks and Piers Clauses Act 1847, which originally limited their jurisdiction to land owned by the Harbour Board, and extending in a one mile radius beyond.

This presented a problem when, in 2011, the Custody Suite operated by Kent Police in Dover closed, meaning that anyone arrested by the Port of Dover Police needed to be transported to the next nearest Custody Centre in Canterbury – and as this meant going further than a mile away from the Port, any such arrest became unlawful once the boundary was past. A specific piece of legislation – the Marine Navigation Act 2013 – was required in order to fix this problem, extending the jurisdiction of all Port Police Forces to the territorial area in which they were located (e.g. Kent, in the case of the Port of Dover Police) but only for the purposes of Port Policing matters, and not wider law enforcement – and no further than that one regional area.

So, if you have been subject to arrest by a Police Officer who does not work for one of the territorial Forces (all of whom are listed here) then it is always worthwhile checking the extent of their jurisdiction. For when Private Policemen conduct themselves like Public Constables, that way lies abuse of power and infringement of civil liberties.

Who are the Mersey Tunnels Police (MTP)?

If you believe you have been wronged by a ‘normal’ Police Officer, who works for one of the 43 territorial Forces of England and Wales, then the correct Defendant to name when you sue them is the Chief Constable of that particular Force (who is answerable to the Crown in the person of the Home Secretary).

If you are bringing a claim arising out of the actions of a Mersey Tunnels Police Officer, then the correct Defendant is the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority.

Mersey Tunnels Police are responsible for the policing of the two road tunnels (“Queensway”, also known as the Birkenhead Tunnel, and “Kingsway”, also known as the Wallasey Tunnel) which connect Liverpool to the Wirral Peninsula. These tunnels were opened in 1934 and 1971 respectively and are both toll roads.

Mersey Tunnels Police Officers derive their powers from Section 105 of the County of Merseyside Act 1980 (as amended by the Local Government Act 1985) which, at paragraph 1, states as follows (my emphasis ) –

“The county council may appoint any of their officers or servants to act as law enforcement officers for the policing of the tunnels, the approaches and any marshalling area.”

Paragraph 3 of the same section clarifies that it is only when so acting that those law enforcement officers “shall have the powers and privileges of a Constable.”

The above legal framework was succinctly summarised in the following “Force Orders” document issued by Mersey Tunnels Police on 1 May 2005 –

- “Officers of Mersey Tunnels Police act in the capacity of a citizen outside of jurisdiction, and if they come across an arrestable offence whilst on duty, but off jurisdiction, are required to notify Merseyside Police, who will allocate an officer to deal with the incident.”

These geographical limitations were further, explicitly, acknowledged in the Partnership Agreement dated 5 August 2014 between Mersey Tunnels Police and Merseyside Police as follows –

- “The jurisdiction of Mersey Tunnels Police is limited to the Mersey Tunnels, the approach roads and Marshalling areas.”

- “The officers have no right to act or to exercise powers for the purpose of dealing with any incident outside of the areas specified [above].”

Those who are given power and authority over others are naturally inclined to exercise and extend it, whether deliberately or not, pushing the boundaries of their power wider in terms of scope, types of activity, level of force, or range of operations (which can of course include geographical range): this is sometimes known as the doctrine of “Mission Creep.”

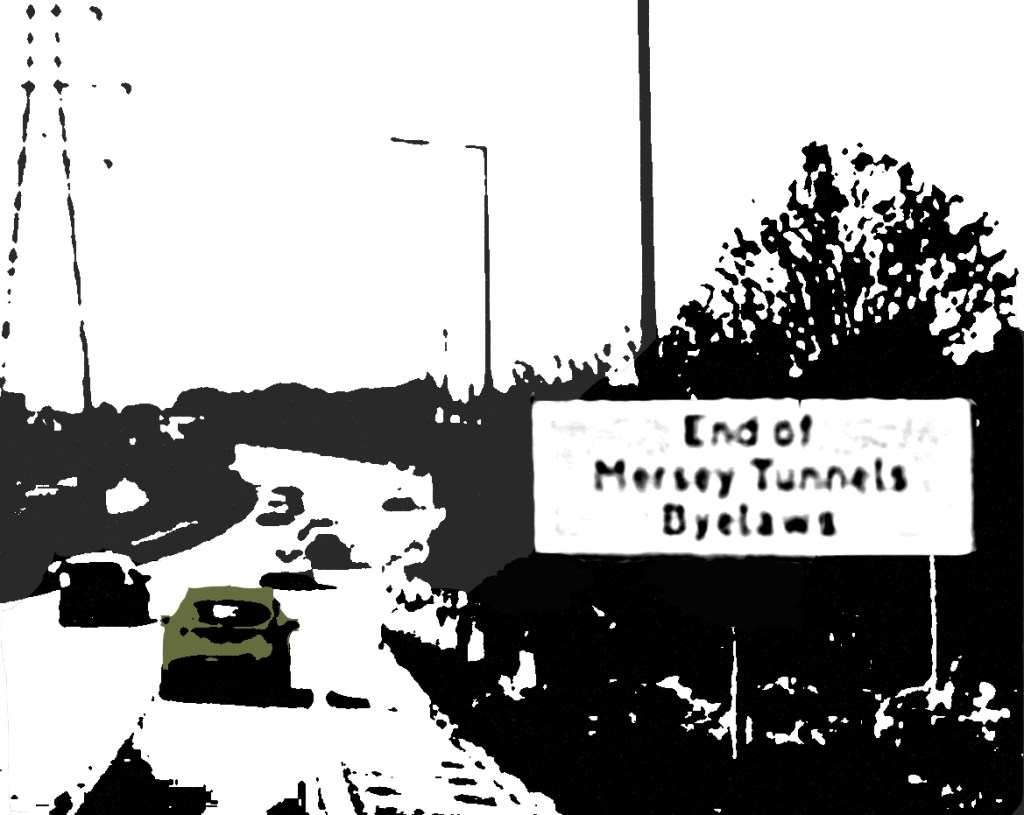

Under the County of Merseyside Act, Mersey Tunnels Police have power over those using the tunnels themselves, the marshalling areas for vehicles using or intending to use the tunnels (e.g on the Toll Plaza around the pay barriers) and their direct ‘approach roads’ – the canyon- like dual carriageways which feed traffic to/ from the tunnels and the M53 motorway and other A- roads. These approach roads are demarcated by signs stating “Start [or “End”] of Mersey Tunnel Byelaws.”

But what about the multiple ‘ordinary’ road bridges which cross over the approach roads and above the marshalling areas, on both the Liverpool and Wirral sides of the river – are these within the jurisdiction of MTP?

Mission Creeps

As a rule of thumb, you can think of the officers of the ‘Special Police Forces’ as being privately funded security guards who provide policing services in particularly defined locations and/or for particularly defined purposes. However, the uniforms that they wear, and the fact that many of their recruits are former ‘ordinary bobbies’ from one of the Home Office Police Forces, can lead these officers to behave exactly as if they were fully- empowered Police Officers, and that was at the root of the problem in the case which I will be addressing in this blog.

One day in November 2020, my client Brian was on the section of Oakdale Road which is carried by a bridge above the Kingsway Tunnel’s approach road ‘cutting’. Oakdale Road is an ordinary residential road through the suburb of Wallasey, consisting of a single carriageway and pedestrian pavements on either side. There is no public access from Oakdale Road to the tunnel, or its approach road, below. As an ordinary public road, and not part of the tunnels estate, it is naturally the case that the Mersey Tunnels byelaws do not apply to Oakdale Road, and its only association with the tunnels is that it overlooks them.

Brian had taken his car to a local garage for minor repairs and went for a walk in the area near to the garage whilst the work was being completed. He was expecting a phone call from the mechanic to notify him when the work was complete. During his walk, Brian stopped on Oakdale Road, overlooking the Kingsway Tunnel entrance, and was reading on his mobile phone, awaiting the call from the garage. This was during the time of Covid but Brian was entirely alone, there were no other people in the vicinity, and he was not conceivably causing any danger to ‘public health.’

However, a Mersey Tunnels Police vehicle now pulled up in Brian’s vicinity and an MTP Sergeant exited the vehicle, and approached Brian, demanding to know what he was doing out in “Lockdown.”

Brian informed the Sergeant that he was awaiting a phone call. The Sergeant demanded his address; my client declined to provide this and queried whether he was being detained. The Sergeant replied that he was not.

Accordingly, Brian crossed to the other side of the road and the Sergeant made no attempt to stop him, but was now joined by another vehicle containing two MTP Constables.

From across the road, Brian requested the officers’ details, as the Sergeant approached him again. My client queried why he was being bothered by the officers, and the extent of their jurisdiction. The Sergeant replied that he had approached Brian because he was “in breach of the Coronavirus Regulations” and told him to return home.

When Brian asked to simply be left alone, the Sergeant then threatened to arrest him if he refused to go home or leave the area as he was “causing a danger to public health” – despite the fact that as with so many of these ‘Coronavirus conflicts’ the danger of infection caused by close proximity of persons was solely being caused by the Officers who were surrounding, intimidating – and threatening to lay hands on a harassed member of the public.

Brian now walked away along Oakdale Road, whilst the Sergeant radioed to his control room, stating that if Brian returned he would “lock him up”. When asked by control what offence the Claimant was suspected of committing, the Sergeant replied “Section 24 breach of Public Health”.

Shortly afterwards, Brian, who was exasperated by the ongoing attentions of the officers, walked back down Oakdale Road, on the other side of the road, and when challenged by the officers called over that he was taking exercise.

Then, as Brian continued to walk away from the officers along Oakdale Road, the Sergeant chased after my client and, coming up from behind him, took hold of his left arm.

Brian was placed in a state of shock by this sudden assault; and although he was in no way fighting back, the two Mersey Tunnels constables ran over to ‘follow the leader.’ The three officers handcuffed Brian, applying considerable force to his arms as they did so, causing him pain. The Sergeant told Brian to “stop resisting” but had not at this point actually told Brian that he was under arrest, or for what offence – making this a prima facie unlawful arrest – even if it had been carried out by Police Officers within their proper jurisdiction. But remember – Officers of Mersey Tunnels Police act in the capacity of a citizen outside of jurisdiction.

Brian felt his arms being twisted and pulled by the officers, and one of them bending his left middle finger, causing him acute pain. Whilst this was ongoing, the Sergeant belatedly informed Brian that he was being arrested for “breaching Coronavirus Regulations”. With both of his hands now in handcuffs, Brian complained that the cuffs were hurting him, to which the Sergeant threatened to take Brian to the ground “if you resist.”

Alarmed by the officers completely over-the-top behaviour, Brian tried to explain that his car was being repaired, that he was awaiting a phone call from the garage, and that it was too far to walk home. However, the Sergeant interrupted this explanation and said that Brian had been back to the bridge two or three times “recording down” and that they were aware that there was a “demonstration” on that day. My client had no knowledge of any ‘demonstration’ and offered to show the officers his phone, to prove that the only recording he had taken was of his initial interaction with the Sergeant.

With a calmer head now perhaps beginning to prevail on his shoulders, the Sergeant began to de- escalate matters. He used his Body Worn Camera (which had captured the above events) to document an injury to Brian’s wrist, caused by the cuffs, and then released my client from those cuffs. Unfortunately, this did not free Brian from the pain which was now spreading down his hand into his fingers.

Brian was then taken to the Sergeant’s car – still under arrest – and made to sit in the rear seat. At this moment, Brian’s phone rang – it was the call from the garage he had been waiting for all along.

The Sergeant now informed Brian that if he provided his details he would be released. Just wanting to go, Brian reluctantly did so and was then “de-arrested” and allowed to leave – walking off in the direction in which he had been heading when the Sergeant had accosted him.

Brian had been detained against his will by the Officers for approximately 15 minutes, and the force used upon him left him feeling physically and mentally shaken.

Furthermore, throughout the length of the interaction between my client and the officers, as described above, several other members of the public passed along Oakdale Road on foot, but none of these people were approached or challenged by any of the three officers as to what their business being ‘out’ might be.

Following the Incident, one of the MTP Constables involved completed a Conflict Management Monitoring form, which contained the following outline of the incident –

“We were asked … to attend Oakdale Road bridge as a male was loitering on the top of the bridge. On arrival SGT was already at scene speaking to the male. The male was refusing to listen to SGT. After a number of attempts to ask the male to leave the area, SGT told the male he was under arrest, and attempted to put handcuffs on his left wrist. The male was asked numerous times to stop resisting. The male eventually stopped when he was told that he was going to be taken to the floor. He was then put into the back of SGT’s police vehicle. The male then agreed to leave the area if he was de-arrested.”

The Sergeant also completed a Conflict Monitoring form in which he admitted that my client was “not assaultive outwardly towards us”.

Advice and Analysis

When Brian consulted my firm for legal advice, we quickly agreed to represent him on a no win, no fee basis.

Leaving aside for a moment the nature of these officers (Mersey Tunnels Police – not Home Office constables), there were obviously strong grounds for a claim for unlawful arrest to be brought on behalf of Brian –

- There were no reasonable grounds to suspect that Brian had committed, or was about to commit, an offence contrary to the Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020 (“Covid Regulations”) or any other laws relating to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Brian’s conduct did not pose any discernible risk to public health such as warranted his arrest. He was standing quietly, alone, outside, minding his own business and even wearing a face covering when he was approached by the officers.

- The arrest was not reasonably necessary in the circumstances for any of the prescribed reasons pursuant to Section 24 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984.

As it happened, however, Brian was already aware of the limited jurisdiction of MTP, and having reviewed the evidence I agreed with his initial belief that the Officers had no power to police this bridge in the first place, whether to enforce Coronavirus regulations or any other law – this was not land that formed part of the Tunnels, approaches or marshalling areas. Accordingly, absent jurisdiction, my client’s arrest was ipso facto unlawful.

What had happened here, to cause the Officers oppressive and excessive conduct, was in my opinion, a ‘perfect storm’ of mission-creep policing caused by the twin elements of the ‘Coronavirus curfew’ (which had enabled the authoritarian impulses of many Police Officers) and the natural (though unlawful) impulses of a “Special Police Force” to push at the limitations of its power, and to try and extend the physical remits of its jurisdiction.

It subsequently transpired that MTP were, on the day in question, on the lookout for “anti- Lockdown” protestors believed to be intending to travel through the tunnels in order to assemble in Liverpool city centre. That seems to be what drew them to my client on the bridge – perhaps they had a fanciful notion that Brian was there to film a convoy of protestors? This was the very definition of “ultra vires” mission creep. Stopping a busload of potential protestors who were actually attempting to drive through the tunnel would have been one thing – interfering with the lawful business of a solitary citizen on an adjacent but ‘out of jurisdiction’ road, was quite another.

What Did Mersey Tunnels Police Try to Argue?

In response to the claim which we presented on behalf of Brian, Mersey Tunnels Police initially strongly stood their ground, arguing that the proximity of Oakdale Road bridge to the tunnels themselves, including the fact that their officers regularly used the bridge when entering/ leaving the tunnels estate (there is a private road from the bridge which connects to the Toll Plaza below, but to which public access is forbidden), meant that their officers had a “reasonable belief” that the bridge lay within their jurisdiction and that it would be “impractical” for them to fulfil their function of maintaining the safety and integrity of the tunnels if they could not operate as police officers on a bridge that passed directly over the tunnel approaches.

Quite rightly, however, the law does not allow the statutorily defined powers of any Police Force to expand on the basis of the “beliefs” of its rank-and-file or wishes of its leadership; Police jurisdiction is not equivalent to “right of way” arguments based on years of usage, nor is it a variant of the arrest powers prescribed by PACE which can be legally deployed when there are ‘honest and reasonable’ (but mistaken) beliefs by an Officer as to the commission of an offence.

The jurisdiction of Mersey Tunnels Police was a black and white matter – for all the attempts of these particular boys in blue to turn it into a ‘grey area.’ Ironically, the case I was arguing on behalf of my client had the support of Merseyside Police themselves in the Partnership Agreement – which jealously preserved the ‘real’ Police Forces prerogative over the rest of Merseyside – including those bridges which happen to run over the tunnel approaches.

If Mersey Tunnels Police want to change that, they will need an Act of Parliament – and it ill- became them to attempt to short-circuit the law by bamboozling the civil courts, in the context of this claim, though that, for a long time, was what they attempted to do – pleading a lengthy Defence, refusing to settle and serving statements from numerous officers, including the Chief Inspector of the Force (the highest ranking MTP Officer – equivalent to a Chief Constable elsewhere, though his bailiwick is considerably smaller).

Why Didn’t They Back Down?

Despite the fact that Brian clearly had a very strong case, MTP declined the opportunity to settle the matter amicably, outside of court, and instead we had to issue court proceedings on behalf of Brian. MTP certainly seemed very happy to blow the public’s toll money on fighting a case they should have agreed to ‘shake hands on’ at the earliest opportunity … but when it comes to civil litigation, Police Forces of all sizes often seem to let their hearts rule their heads. This seems to be born out of an almost “Trollish” animosity towards that very public they are supposed to be serving – should the public claim or complain about them.

Brian’s case was listed for trial, when only days before the Pre- Trial Review, MTP finally agreed to settle his claim for substantial damages plus legal costs.

Thankfully, my client knew his rights from day one in this matter, but not everyone would – and the Police frequently misrepresent the extent of their powers (e.g whether or not they have a power to detain you – Home Office or not…).

When it comes to Special Police Forces, with special jurisdictions, take special care – in the form of expert advice from myself or my colleagues.

My client’s name has been changed.

For many years, I have relied on the strength of this blog, my case results, and the recommendation of my clients – not expensive advertising designed to ‘game’ search results – to build awareness of my work. If you believe this site provides valuable information and an insightful perspective, please help me continue by leaving a 5 star review. Your review plays a vital role in ensuring that those in need can find the right solicitor for their case. Thank you!

You must be logged in to post a comment.